What is breast cancer?

In 2018, breast cancer was the most frequently diagnosed cancer and the second most common cause of cancer deaths in Ontario women.* In Ontario, breast cancer usually develops later in life, with 83% of cases diagnosed in women age 50 and older.

In Ontario, breast cancer usually develops later in life, with 83% of cases diagnosed in women age 50 and older.

People who are assigned male at birth can also get breast cancer, but it's much less common.

*The source of data used in the My CancerIQ Breast Cancer Risk Assessment is based on people who were assigned female at birth. Because of this, gender binary language (male, female, man, woman) may sometimes be used. It’s also important to note that the word "chest" is sometimes used when describing the breasts. Some people, including trans men, transmasculine people and nonbinary people, may prefer the term "chest". The term “breast” is still used to make sure the language is clear for everyone. If your gender is different from your sex assigned at birth, My CancerIQ may not assess your risk accurately. Talk to your doctor or nurse practitioner about your personal risk of developing breast cancer.

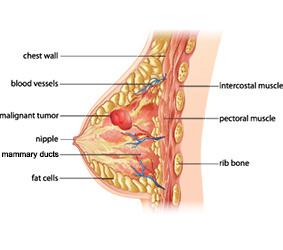

The breast is a complex structure. It contains glands that make milk (lobules), tubes to carry milk from the lobules to the nipple (ducts), fibrous supportive tissue, blood vessels, vessels that carry lymph fluid to the lymph nodes (located under the arm, near the collarbone and in the chest behind the breastbone), and fatty tissue.

Most lumps in the breast are benign, meaning they are not cancerous. Such lumps are caused by fibrous scar-like tissue or are fluid-filled sacs or cysts.

If a lump or a tumour in the breast is malignant, it means it has become cancerous. In cancer, the cells divide uncontrollably and can invade surrounding tissue. Cancerous cells can sometimes spread (metastasize) to other parts of the body.

Breast cancer can occur before menstruation stops (pre-menopausal breast cancer) or after menopause (post-menopausal breast cancer). Although many of the risk factors (habits or personal characteristics that may increase the chance of getting cancer) for pre- and post-menopausal breast cancer are the same, there is growing evidence suggesting there are differences as well. For example, genetic and other medical factors may have a greater effect on the development of pre-menopausal breast cancer, and lifestyle factors may play a greater role in post-menopausal breast cancer. More research is needed to fully understand the differences between pre- and post-menopausal breast cancer.

Risk factors you can change or control

-

Smoking

Although we most often think of smoking as a cause of lung cancer, smoking increases the risk of developing many types of cancer, including breast cancer. Cigarette smoke contains over 70 chemicals that are known to cause cancer. There is no safe level of smoking.

Alcohol consumption

For breast cancer, there is no safe level of alcohol consumption; even drinking small amounts of alcohol can increase your risk of developing breast cancer. Alcohol may damage the DNA of cells or allow other cancer-causing substances to more easily enter cells. There is also evidence suggesting that alcohol increases the level of estrogen in the blood, which can stimulate the growth of some tumours.

Adult weight gain

Gaining body fat as an adult may increase the level of several hormones, including estrogen, and may stimulate cell growth. Avoiding gaining large amounts of body fat can help reduce your risk of breast cancer.

-

Diet

Some evidence suggests a diet rich in vegetables and fruits may help reduce the risk of breast cancer. The reasons are not yet clear. Vegetables and fruit are good sources of beneficial nutrients such as antioxidants, carotenoids and phytochemicals that help to boost the immune system. Vegetables and fruit can also help to prevent nutritional deficiencies, provide people with natural sources of cancer-fighting vitamins and help people stay healthy.

Physical activity

Physical activity may reduce the risk of breast cancer. The exact reasons why exercise may reduce breast cancer risk aren’t clear. Physical activity may protect against breast cancer by helping to regulate the levels of hormones and steroids circulating in the blood. It may also help prevent gaining body fat.

Prescription medications that contain female hormones

Oral contraceptives:

Compared to people who have never taken oral contraceptives (birth control pills), those who do – or who have taken them in the past – may have a greater risk of breast cancer. When you stop taking oral contraceptives, your risk of breast cancer starts to decline. It’s important to talk with your doctor or nurse practitioner about both the risks and the benefits of oral contraceptives.

Hormone replacement therapy (HRT):

Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) may be used to treat the symptoms of menopause such as hot flashes. Taking HRT, especially prolonged use of the combined form containing both estrogen and progesterone, may increase your risk of breast cancer. Your risk falls after HRT is stopped. If you are taking HRT, talk to your doctor or nurse practitioner about both the risks and the benefits of this medication.

Risk factors you can't change or control

History of benign breast disease

Many people who were assigned female at birth have non-cancerous (benign) breast conditions, which may appear as irregular lumps or cysts (fluid-filled sacs) in the breast. If your doctor has said you have benign breast disease it means it is not cancer. However, some types of benign breast disease may increase your risk of developing breast cancer.

Genetics

Genetic variants

Every cell contains a genetic blueprint in the form of DNA. DNA tells the cell when to reproduce (make new cells), when to stop making new cells and how to make proteins that the cell needs. A genetic variant is a permanent change in the DNA of the cell. Some variants (also known as mutations) may affect how a gene works. Variants can occur by chance when cells reproduce or because of damage to the DNA. Variants can also be inherited from a parent (i.e., hereditary genetic variants).

If someone has a hereditary genetic variant, it can significantly increase their chance of getting breast cancer in their lifetime. But these types of variants are rare and only occur in less than 1% of the population. Probably the best-known variants are of the BRCA genes (BRCA1 and BRCA2). If someone has a BRCA1 or BRCA2 variant, their lifetime risk of developing breast cancer is 55% to 65%; for BRCA2, the risk may be 45% to 49%. In addition, BRCA1 and BRCA2 variants are associated with an increased risk of other cancers, such as ovarian and pancreatic cancer. Variants of other genes (e.g., TP53 or PALB2) can also increase the risk of breast cancer.

If you have a closely related family member (e.g., parent, sibling such as brother or sister, child, grandparent, aunt, uncle, niece or nephew) who have been tested and told they have a known genetic variant for breast or ovarian cancer, there is a possibility you may also carry the same variant. Talk with your doctor or nurse practitioner to find out more.

Family history

Having a closely related family member (e.g., parent, sibling such as brother or sister, child, grandparent, aunt, uncle, niece or nephew) diagnosed with breast, ovarian and/or prostate cancer – especially if the cancer was diagnosed at a young age – may increase your risk of developing breast, ovarian and/or prostate cancer in the family. Talk with your doctor or nurse practitioner to find out more.

Ashkenazi Jewish heritage

People of Ashkenazi Jewish descent are more likely to have genetic variants that can increase the risk of breast cancer. If you are of Ashkenazi Jewish descent, talk with your doctor or nurse practitioner about your risk of breast cancer.

-

Reproductive history – menstruation, menopause, pregnancy and breastfeeding or chestfeeding

Hormones, especially estrogen, can encourage the growth of some types of breast cancers. The lifetime exposure to estrogen is lower in people who:

- start menstruating at a later age.

- go through menopause at an earlier age.

In general, starting to menstruate at a younger age or going through menopause much later in life is associated with a greater relative risk of breast cancer. Less lifetime exposure to estrogen may help to lower the risk of some types of breast cancer.

When people are pregnant, changes occur in the cells of the breast to prepare for breastfeeding or chestfeeding.* These changes can make the cells more resistant to cancer later in life. The earlier in life someone experiences these changes, the greater protection they have against breast cancer. As a result, people are at lower risk of breast cancer if they have:

- given birth, particularly if they have given birth at an earlier age or have given birth to several children.

- breastfed or chestfed, particularly for a combined total of a year or more.

Talk with your doctor or nurse practitioner to find out more about your risk.

*The word "chestfeeding" may be used by some people, including trans men, transmasculine people and nonbinary people, to describe the process of nursing. The term “breastfeeding” is still used to make sure the language is clear for everyone.

-

Breast (chest) density

Breast tissue is made up of dense and fatty tissue. Dense tissue, or fibroglandular tissue, is made up of ducts, glands for making milk and supportive tissue. Breast (chest) density is measured by how much dense tissue a breast has compared to fatty tissue.

Breast (chest) density is determined when you get a mammogram. In Ontario, breast (chest) density is reported as a Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) category. BI-RADS has 4 breast density types (or categories) (A, B, C and D) ranging from the least amount of dense tissue to the most amount of dense tissue. People with higher density have an increased risk of developing breast cancer. Dense tissue can also make it harder to find breast cancer on a mammogram.

Breast (chest) density cannot be changed but it can be affected by other factors such as age, menopause and hormone replacement therapy. If you have dense breasts and have concerns about your risk of developing breast cancer, talk with your doctor or nurse practitioner about breast cancer screening recommendations.

-

Chest radiation

Radiation therapy is used to treat certain cancers, such as lymphoma, and in the past was used to treat diseases or conditions such as tuberculosis, postpartum mastitis, acne or an enlarged thymus gland. Receiving ionizing radiation therapy to the chest before age 30 and at least 8 years ago may increase the risk of breast cancer. The risk is higher for people who were treated during puberty. Talk with your doctor or nurse practitioner to find out more.

Prescription medications – tamoxifen and raloxifene

Tamoxifen and raloxifene are prescription medications that block the effects of estrogen. They may be prescribed to treat breast cancer, to help prevent breast cancer in people at high risk, or to prevent bone-thinning (osteoporosis). Taking tamoxifen or raloxifene for five or more years may lower your risk of getting a new breast cancer or recurrence of a first breast cancer. These medications have risks and benefits, so they are not appropriate for everyone. Other medications may also affect your risk of breast cancer. Talk with your doctor or nurse practitioner to find out more.

Common brand names for tamoxifen include Nolvadex D®, Mylan-Tamoxifen®, Apo-Tamox®, Tamoxifene®, Teva-Tamoxifen®. Brand names for raloxifene include Evista®, Apo-Raloxifene®, Teva-Raloxifene®.

-

Height

Studies suggest that people who were assigned female at birth and who are taller than 5 feet and 7 inches may have a higher risk of developing breast cancer after menopause. The reasons aren’t clear, but they may reflect the influence of hormones and possibly a higher energy intake during early life.

-

Weight when you were born

People who were assigned female at birth and were heavier than average at birth (usually defined as weighing more than 8.5 pounds) may have a slightly higher risk of breast cancer before menopause. The reasons for this are not clear. It may reflect the effect of exposure before birth to higher levels of hormones circulating in the blood of the mother.

-

Weight when you were 7 years old

People who were assigned female at birth and were overweight at about age 7 may tend to have a lower risk of breast cancer. The reasons for this are not clear. It may be because hormone levels that change with weight gain have different effects depending on your age.

What you can do to protect yourself

Screening:

The Ontario Breast Screening Program (OBSP)

The Ontario Breast Screening Program (OBSP) is a screening program that encourages people in Ontario to get screened for breast cancer. The program screens 2 different groups of people who are eligible for breast cancer screening in Ontario: those at average risk and those at high risk.

People at average risk:

Women, Two-Spirit people, trans people and nonbinary people ages 40 to 74 are eligible for screening through the OBSP if they:

- have no new breast cancer symptoms;

- have no personal history of breast cancer;

- have not had a mastectomy;

- have not had a screening mammogram within the last 11 months; or

- have used feminizing hormones for at least 5 years in a row if they are transfeminine.

Screening has been shown to be effective when eligible people in who are at average risk of developing breast cancer get mammography every 2 years.

People ages 40 to 49 have a lower chance of getting breast cancer than people ages 50 to 74. The balance of potential benefits to potential harms of breast cancer screening for people ages 40 to 49 may be different than for people ages 50 to 74, so people ages 40 to 49 should make an informed decision about whether breast cancer screening is right for them. To help make an informed decision about getting screened, the OBSP encourages people to talk with their doctor, nurse practitioner or a Health811 navigator about their personal risk for breast cancer, the potential benefits and potential harms of breast cancer screening, and what matters most to them in taking care of their health.

If you want, you can be referred (sent) by your doctor or nurse practitioner. But you do not need a referral and you can make your own appointment. Find your nearest Breast Screening Program location.

People over age 74 can be screened in the OBSP but are encouraged to make a personal decision about breast cancer screening in consultation with their doctor or nurse practitioner. People over age 74 need to be referred (sent) by their doctor or nurse practitioner for each screening mammogram. The OBSP will not invite people over age 74 to participate in the program.

Learn more:

- Cancer Care Ontario - The Ontario Breast Screening Program.

- Cancer Care Ontario - Get Checked for Cancer.

- Cancer Care Ontario - Breast Density.

- To find Indigenous-led health centres, visit iphcc.ca/meet-our-members or afhto.ca/find-team-near-you.

People at high risk:

The High Risk Ontario Breast Screening Program (OBSP) is designed for people ages 30 to 69 who are identified as being at high risk for breast cancer. It is recommended that people at high risk for breast cancer get screened for breast cancer with annual mammography and breast MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) (or breast ultrasound if MRI is not medically appropriate). Women, Two-Spirit people, trans people and nonbinary people can be referred (sent) to the High Risk OBSP if one of the following criteria is met:

- Known carrier of a pathogenic or likely pathogenic gene variant (e.g., BRCA1, BRCA2, TP53, PALB2) that increases their risk for breast cancer;

- Have not had genetic testing, but have had genetic counselling because they are a first-degree relative of a carrier of a pathogenic or likely pathogenic variant (e.g., BRCA1, BRCA2, TP53, PALB2) that increases their risk for breast cancer;

- Previously assessed by a genetics clinic (using the IBIS or CanRisk risk assessment tools) as having a 25% or greater lifetime risk for breast cancer based on personal and family history; and/or

- Have had radiation therapy to the chest to treat another cancer (e.g., Hodgkin lymphoma) before age 30 and at least 8 years ago.

You must be referred, or sent, by your doctor or nurse practitioner to the High Risk OBSP.

Learn more:

- Ontario Breast Screening Program screening for people at high risk.

- For help finding a family doctor or nurse practitioner, call Health811 at 811 (TTY: 1-866-797-0007) or visit ontario.ca/healthcareconnect.

- To find Indigenous-led health centres, visit iphcc.ca/meet-our-members or afhto.ca/find-team-near-you.

Genetic testing

Genetic testing can check to see if you have a genetic variant that increases your risk of breast cancer. Genetic testing may be appropriate if you are diagnosed with breast cancer at or before age 45 or have a strong family history of breast and/or ovarian or related cancers. Related cancers may include prostate cancer, pancreatic cancer and others. The more relatives with a history of cancer and the younger the age at diagnosis, the greater the likelihood that a genetic variant may be present. The risk of having a genetic variant is also higher for people with a family history of male breast cancer and people who are of Ashkenazi Jewish descent. Please speak to your doctor or nurse practitioner to see if genetic counselling or genetic testing is appropriate for you.

Learn more

- For more information on genetic testing, please visit the Canadian Cancer Society’s website.

- Learn more about the High Risk Ontario Breast Screening Program and services.

- Your doctor or nurse practitioner may use the Ontario Health - Cancer Genetic Assessment Referral Guidance to assess if genetic testing is right for you.

If you take artificial hormones, talk with your doctor or nurse practitioner

The artificial hormones in oral contraceptives and hormone replacement therapy may increase the risk of breast cancer. If you take either medication, talk with your doctor or nurse practitioner about the risks and benefits of treatment.

Be breast aware

The Ontario Breast Screening Program recommends that everyone be breast aware. Someone who is breast aware knows how their breasts normally look and feel so that they are more likely to notice any unusual changes. As breast cancer develops over time, the following changes may occur:

- A new lump or dimpling on the breast;

- New changes in the nipple or fluid coming from the nipple,

- New redness or skin changes that do not go away; or

- Any other new changes in the breasts.

If you notice any changes in your breasts or have concerns, see your doctor or nurse practitioner, regardless of your age. Most changes are not cancer, but they should be checked right away.

Learn more:

Limit your alcohol

Research suggests that when it comes to breast cancer, there is no safe level of drinking. To reduce your risk of breast cancer, you may want to stop drinking or drink less frequently.

Tips for cutting back

- Set aside more days each week as non-drinking days.

- Plan ahead on how you will reduce your alcohol consumption or handle the urge to drink.

- Know the standard drink sizes to accurately track how much you drink.

- Switch to non-alcoholic drinks after you have reached your limit.

If you have trouble cutting down or quitting, there are lots of free resources to help.

Learn more

- The Canadian Cancer Society - Limit Alcohol.

- For help with alcohol addiction: ConnexOntario - Health Services Information for Ontarians.

- Ontario Health's quality standard on Problematic Alcohol Use and Alcohol Use Disorder.

Be smoke-free

If you do not smoke cigarettes, you have avoided an important cancer risk factor. To keep yourself safe, also try to avoid other people’s cigarette smoke (second-hand smoke).

If you smoke cigarettes, you have probably heard that quitting will help to improve your health and reduce your risk of cancer and other serious diseases. The good news is that it is never too late to benefit from becoming smoke-free.

It can be hard to quit smoking and often it takes more than one attempt, but more than two-thirds of Canadians who used to smoke have been able to stop smoking for good. Six out of 10 people used a smoking cessation aid, such as nicotine replacement therapy, quit smoking programs or medication. Talk with your doctor, nurse practitioner or pharmacist about the many options to help become smoke-free.

Here are some tips if you smoke and are planning to quit

- Write down or think about how you would feel if you could quit. For example, would you feel better about yourself and more in control of your life? Would it make you a better role model to your children or loved ones? Would it give you a better chance of living to enjoy a healthy retirement? Think about what your life would be like if you could quit and your reasons for wanting to stop.

- Keep track of your smoking. Sometimes, seeing how much you are smoking — and being more aware of when you are reaching for a cigarette — can help you to cut back. Keep a count of every cigarette you smoke on your cell phone, on a piece of paper or on your computer.

- Book an appointment with your doctor or nurse practitioner or talk with your pharmacist about smoking cessation aids and programs that might make it easier for you to quit. Investigate all your options so you can think about what you may do in the future.

- Planning is the key to success. Develop a plan for how you will quit (cutting down, cold turkey, or using a smoking cessation aid), when you will start (your quit date), and who will help you and be your quit smoking buddy or coach. Your quit smoking buddy or coach should be someone who will be sympathetic but firm to help you stay on track.

- Knowing how much your smoking is costing you may give you motivation to quit. Find out with the Healthy Canadians Cost Calculator.

Learn more about how to become and stay smoke-free or how you can help someone you care about to quit:

- Speak to a Quit Coach at Health811 for quit smoking support by calling 811, TTY 1-866-797-0007.

- Visit Smokers’ Helpline to join an online chat forum with people planning to quit, people who have quit, Quit Coaches and to view additional resources. You can also text iQuit to the number 123456 (in Ontario) for quit support.

- Visit the Ontario Ministry of Health’s Quit Smoking website.

- Visit Health Canada’s On the Road to Quitting program.

- Visit QuitMap.ca to find a quit smoking counsellor or group in your community.

- Visit Make Your Home and Car Smoke-Free.

- Visit the Indigenous Tobacco Program website to access resources for First Nations, Inuit, Métis and urban Indigenous peoples.

Eat healthy food

Studies suggest that eating vegetables and fruit may help to reduce the risk of breast and other cancers. It can also help reduce your risk of other serious chronic diseases, such as diabetes and heart disease.

Tips

- Keep a bowl of fruit in the kitchen so you can easily grab one when hungry or while leaving the house.

- Challenge yourself or your family to try a new vegetable or fruit each week.

- In the morning, add fruit to your cereal or yogurt or vegetables to your omelette.

- Add crushed pineapple to coleslaw or add orange sections or grapes in a tossed salad.

- For dessert, have baked apples or pears or a fruit salad.

- Pull out your blender and make fruit smoothies by blending fat-free or low-fat yogurt or milk with fresh or frozen fruit.

- During the summer and fall, support local farmers by buying fruit at a farmer's market or road-side stand. To add some activity to your day, visit pick-your-own farms.

- Remember that frozen vegetables and fruit with little or no added sugar, fat or salt can be low-cost and healthy options.

Learn more:

- Visit UnlockFood.ca to get tips for planning meals and snacks, portion sizes, and healthy recipes to try at home.

- Call Health811 at 811 (TTY 1-866-797-0007) to speak to a Registered Dietitian for free.

Reduce body fat

Large amounts of body fat can increase the risk of breast cancer after menopause. The good news is that small changes in what you eat and physical activity can lead to a modest reduction in fat – and the reduction of breast cancer risk. Making small but consistent changes is a lot safer – and is more likely to lead to long-term success – than going on some extreme diet or weight loss plan.

Some tried-and-true methods to lose body fat include:

- Cutting down on portion sizes, eating a variety of vegetables and fruit and avoiding high-fat foods.

- Eating at regular intervals throughout the day (78% report they eat breakfast every day).

- Tracking your weight regularly (75% say they weigh themselves at least once a week).

- Regular physical activity. The most common form of activity was walking and many reported breaking their activity into chunks throughout the day or incorporating it into their everyday routine, such as walking to work.

Learn more:

- Get tips for healthy eating at UnlockFood.ca.

- You can speak for free with a Registered Dietitian by calling Health811 at 811 (TTY 1-866-797-0007). Ask about programs or resources available in your community or through your local Public Health Unit.

- Find out about Body Mass Index and the relationship between weight and health at Canadian Cancer Society's website.

Be physically active

Being physically active can help you stay healthy and reduce your risk of a number of serious diseases, including breast and colorectal cancer, heart disease and diabetes, help to relieve stress and improve mood. Health Canada recommends that adults 18 to 64 years of age be moderately to vigorously active for at least 2.5 hours (150 minutes) a week.

Tips

- Try to develop a menu of different activities you enjoy that also help to build aerobic capacity, muscular strength and endurance, and flexibility. For example:

- Brisk walking.

- Resistance training.

- Yoga.

- Whenever possible, walk or bike to work, to go shopping, or when moving around your neighbourhood.

- If you dislike exercising alone, involve your partner or family, join a team, find a walking buddy, or take part in sports or recreational activities. Check out your local municipal recreation centre or YMCA/YWCA for classes and groups.

- Make back-up plans for when you face challenges. For example, if the weather means you can't go walking outside, substitute yoga or resistance training.

Learn more:

- Public Health Agency of Canada - Being Active.

- ParticipACTION.

- Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology - 24-Hour Movement Guidelines.

- If you haven't been active for a while, you may want to complete the Get Active Questionnaire and discuss the results with your doctor or nurse practitioner.